From Minecraft to IoT malware: How gamers enslave connected devicesFrom Minecraft to IoT malware: How gamers enslave connected devices

While ransomware attacks loomed large in the first half of 2017, IoT malware continues to spread, thanks in part to young hackers eyeing the competitive video game industry.

September 7, 2017

In the seminal 1983 cybersecurity movie WarGames, an underachieving high school student named David Lightman (played by Matthew Broderick) nearly starts World War III after attempting to play an unreleased video game online. In the process, Lightman discovers the command prompt for a remote military computer after using an automated dialer to call every phone number in Sunnyvale, California. His war dialing effort intended to locate a remote terminal linked to a gaming company based in the city. Instead, he discovers a military computer that runs World War III simulations. “Let’s play Global Thermonuclear War,” he types into the telnet-like terminal, starting a simulation that fools the U.S. military into thinking it is the real deal.

The film has had tremendous relevance to the field of computer security, helping shape U.S. cybersecurity policy in the 1980s, mainstream computer culture and influenced the hacking lexicon.

IoT botnet games

In the IoT realm, the worlds of video games, hacking and youth collide in a “WarGames”-like manner. World War III may not hang in the balance, but evidence suggests that angry gamers used the open-sourced Mirai IoT botnet to target game servers — bringing down a significant chunk of the internet as collateral damage. In fact, the bulk of IoT malware may come mostly from “amateurs, gamers, young people, and attention seekers,” as Flashpoint security researchers Allison Nixon and Pierre Lamy have written.

[IoT Security Summit, co-located with Blockchain360 and Cloud Security Summit, explores how industry-wide security, privacy and trust can be established to unlock the full potential of IoT. Get your ticket now.]

A recent example illustrating a similar theme comes courtesy of an IoT malware purveyor who claims to be 13. Ankit Anubhav, principal security researcher at NewSky Security, reached out to the individual to learn more about how such malcode spreads across the internet. “Posing as a gamer, I asked him about the IoT botnet he had developed,” he said. “I then told him that it was wrong and he said: ‘I am just 13. Cops can’t do anything about it and no law would apply to me.’”

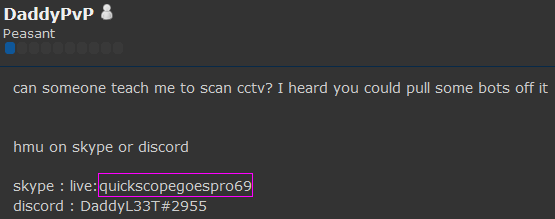

Going by the pseudonym DaddyPvP, the teenager created a website with the URL Daddyhackingteam.com that hosts IoT botnet source code, dozens of remote access terminals, a rootkit named after a Pokémon character and line-by-line tutorials on how to launch several other attacks. The Daddyhackingteam site also serves as a command and control server for an active IoT botnet.

From Minecraft to malware

Anubhav said that, as of July, the owner of the Daddyhackingteam website had been looking for a job as either an administrator or web developer for a server for the Microsoft video game Minecraft with more than 55 million players. The individual stated he was online for 15 to 18 hours each day and could spend the bulk of his waking hours working on the server — at least until school started again in the fall. Incidentally, one of the most frequent targets of botnets — IoT-based or otherwise — are Minecraft servers.

“After that, he changed his mind and started an IoT botnet,” Anubhav explained. In a conversation over Skype, the teenager stated he had 300 IoT bots in his army. He had hoped to enslave IP cameras to add to his botnet, looking for help on the cybersecurity forum Hackforums.net, but had difficulty doing so.

“The funny part is that he used the same contact information for applying for work that he did when discussing his malware [code].”

Incidentally, the modus operandi of IoT botnets is to look for weak or default telnet usernames and passwords, which is a similar vulnerability highlighted in the WarGames film — the password for the war computer was simply the name of its creator’s son: “joshua.” Anubhav recently located a trove of 33,138 telnet device credentials on the site Pastebin.com, thousands of used “admin” as both the username and password.

The DDoS market is so large and open that it is straightforward for even inexperienced hackers to cobble together the code needed to launch botnets. “It’s literally child’s play to set up an IoT botnet,” Anubhav said, adding that the botnet code on the Daddyhackingteam site borrows heavily from a botnet known as Gr1n.

Recently, the British publication Business Matters explained that another teenager reportedly launched 1.7 million DDoS attacks against 660,000 IP addresses — many belonging to gaming websites owned by Sony and Microsoft.

Peter Tran, RSA’s Advanced Cyber Defense general manager and senior director, sees the hacking marketplace growing even more accessible to would-be cybercriminals. “The malware market is becoming like the consumer electronics ‘big box stores’ where you can get technical or customer support for a malware kit you purchase in the underground,” Tran said. “IoT is the new ‘designer malware’ focus with great hacker market promise. It doesn’t matter if you have good or bad skills. IoT malware-as-a-service is becoming a recognized model,” he added. “Much like how Minecraft or Legos work, this type of malware is based on the ability to quickly interchange building blocks to create new variations on demand.”

About the Author

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)