An Engineer Shows How Data Can Trump Conventional WisdomAn Engineer Shows How Data Can Trump Conventional Wisdom

An engineer’s open-source IoT system is leading to better water management at a vineyard, and with the help of data challenging notions about traditional irrigation techniques.

April 2, 2016

By Renier Van der Lee

Necessity is often the motherhood of invention, and that was the case when I realized I needed to better manage irrigation in my Southern California vineyard.

Using an Internet-connected soil monitoring system that I developed, I saved 25%—430,000 gallons—of irrigation water in 2015.

I bought this vineyard in 2010, which was a good year with a lot of rain. But my first harvest was very low yield—half the 3 to 4 tons that are typical for this region. I am paid by the weight of the harvest, and if the yield does not cover my costs, I will get into more than a little trouble with my wife.

One of the challenges I had was that the vineyard had not been very well maintained, in fact it was a distressed property, and the bank didn’t care much about watering grapevines. So I hired a management company to help improve the health of my vineyard.

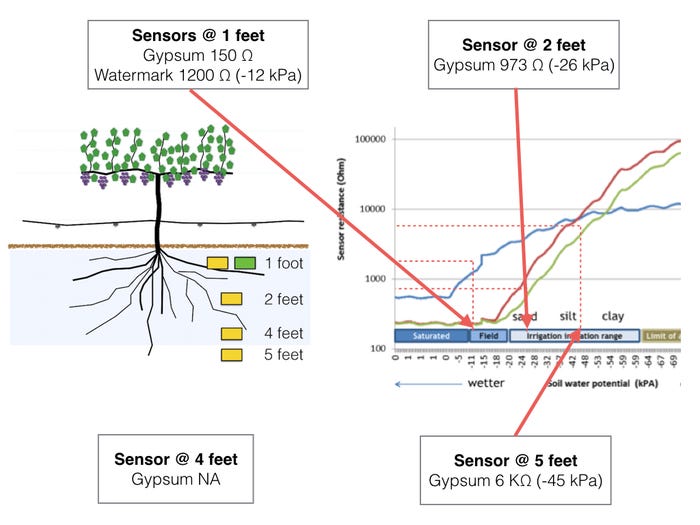

Measuring soil moisture at only the depth of a grapevine’s roots is insufficient, because by the time the sensor detects water, the soil layer above is already saturated. Vanderlee’s system uses sensors at two and four inches and one sensor at 5 ft, below the active root zone. Because the trick is to avoid water draining below the roots of the plants, this sensor should never get wet.

I was amazed when I saw what those guys were doing. The worker in charge of watering didn’t measure anything. He just looked at the vineyard and he knew, presumably by experience, when to turn the irrigation valves on. He’d come back a day or two later to turn them off.

I respect experience and conventional wisdom, but I knew I would never be able to replicate it. And I wondered if there might be a way that I could better manage and measure it. The only way I knew how much water was being used was by looking at my monthly water bill—which was significant.

Hoping to get a better handle on my expenses and improve the health of my vineyard, I read up on techniques for measuring and managing soil moisture.

As a small grower, I couldn’t afford to buy any commercial service. But I do have an electronics background, and I was thinking maybe I could develop something to measure the soil moisture myself.

I started getting interested in how water travels through the soil and how a plant takes it up. I learned from talking to other vineyard managers that a grapevine’s roots are only about four feet deep and that below 5 feet you actually don’t have a lot of uptake on water.

Measuring soil moisture at only the depth of the roots does not give you the data you need, because by the time a sensor detects water, the soil layer above is already saturated. Any additional water is just wasted, because it seeps below the root zone and directs nutrients out of the plant’s reach.

The system I built uses sensors at depths of two and four inches in the active root zone. After irrigation, these sensors should indicate a sufficient moisture level. There is also a sensor at 5 feet, below the active root zone. The trick is to avoid water draining below the roots of the plants, so this sensor should never get wet.

Chart on left shows the soil moisture as measured with sensors at 1, 2 and 5 feet depth just before harvest. The graph on the right shows a calibration comparison between two gypsum sensors (red and green lines), and a commercial Watermark sensor (blue line). With this graph, you can translate sensor resistance (Ohm) to soil water potential (kPa).

My device, called the Vinduino, uses an Arduino Pro Mini single-board computer to transmit data from the soil moisture sensors to the Internet over a 4G hotspot, avoiding any manual data collection and allowing me to track trends.

A system developed by UC Davis calculates the amount of water needed per vine based on weather-station data. Common practice is to water only once a week, but I decided to water every day in order to give the plants a better chance to pick up all the moisture. And I was curious if I could save water by taking measurements at frequent intervals (every 60 seconds), observing the trends, and adjusting the irrigation times accordingly.

New developments of the Vinduino project this year include using long-range radio modules. The previous version used WiFi, which has a limited range, often not enough to cover a vineyard. With this new technology, it is potentially possible to connect hundreds of sensor modules within a 6-mile radius. Farmers can share a gateway, reducing cost for a network infrastructure.

The Vinduino uses very low-cost gypsum sensors, and open-source components, saving thousands of dollars compared to proprietary commercial systems, and is easy to build, making soil moisture measurement available to small growers.

With more vineyards using this technology, we can share data and come up with the best irrigation practices. It very well could be that watering every day is not the best option; maybe it’s every other day.

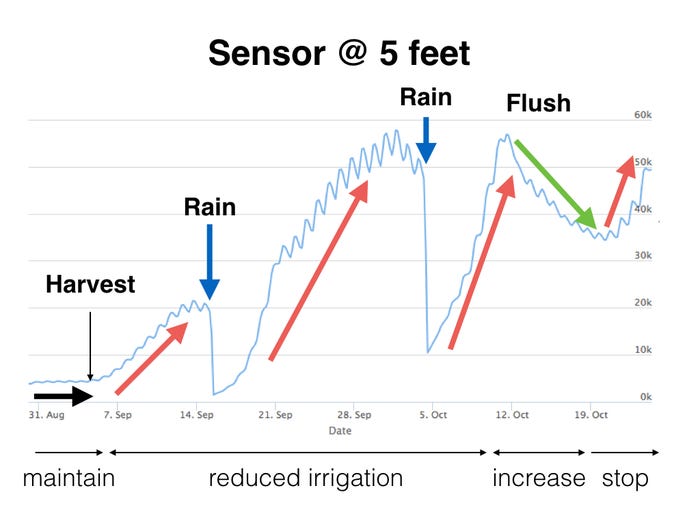

I must confess I am a bit mystified by the data I am collecting on rain, which shows much more rapid moisture penetration through the soil than irrigation. I guess I’ll need to consult a soil expert!

A data mystery: This image shows how the soil moisture at 5 feet depth after harvest, 1st week of September 2015. You can see two rain events where water reaches 5 feet really fast, where increasing the irrigation volume (flush) shows a slow increase in soil moisture.

Of course, the proof of the pudding is in the eating. At this moment, we are pretty busy with preparations for a first trial installation of the new long-range system at a larger winery in April.

Article was originally published on Electronic Design.

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)