Why Arm Sees the BBC Micro:bit as a Global Educational ToolWhy Arm Sees the BBC Micro:bit as a Global Educational Tool

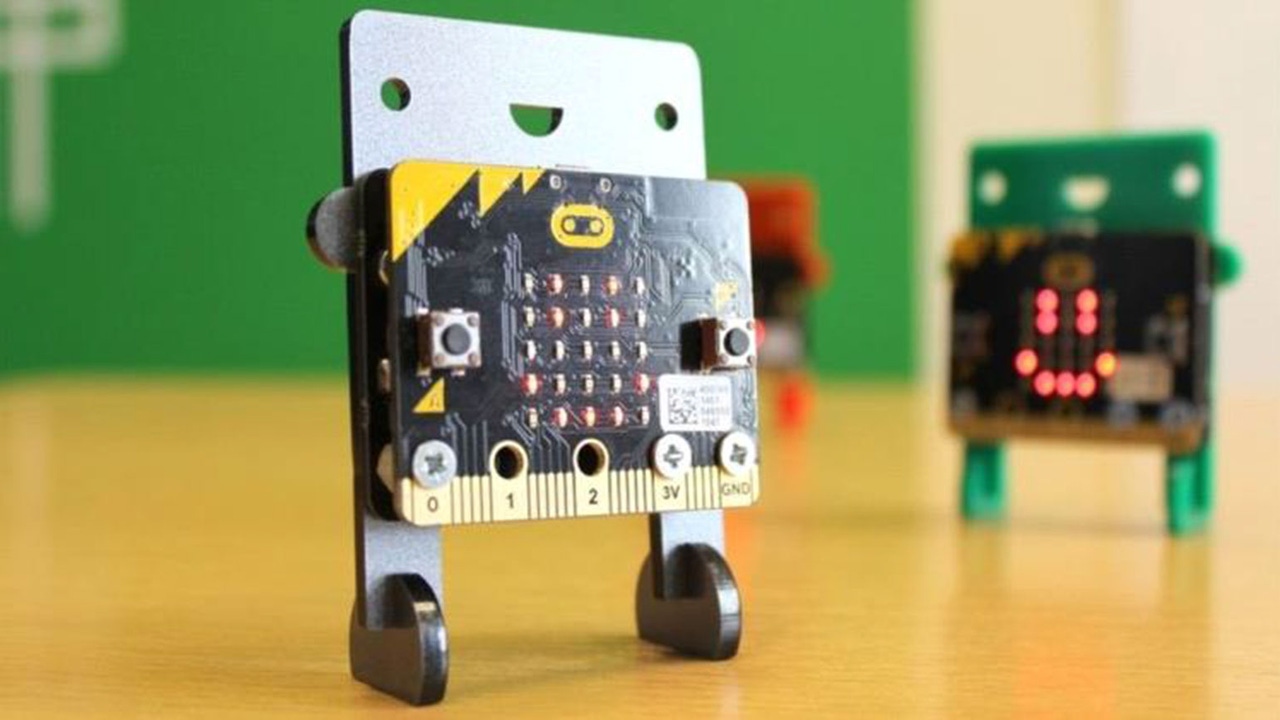

The chip designer’s support of the BBC Micro:bit could inspire the next generation of hardware and software designers.

September 26, 2018

If you ask Zach Shelby, vice president of developers, IoT services group at Arm about what the company is doing to help drive long-term Internet of Things adoption, he is likely to tell you about the Micro:bit Educational Foundation, an organization he found to help globalize hardware intended to help teach the next generation tech skills. To date, millions of children in more than 50 countries have used the BBC Micro:bit. The platform, which was created jointly by the British Broadcasting Corporation, Arm, Microsoft and Samsung, was partly inspired by an earlier generation of computers that helped train legions of developers. “The Commodore 64 and the BBC Micro in the 1980s helped inspire not just technology consumption but technology invention,” Shelby said. “A lot of what kids do today is really technology consumption. They think if they are doing an Instagram post that they are creating technology.”

The Micro:bit Educational Foundation is impressive not just for its relatively small footprint and price point (it can be had for $15) but its potential to inspire creativity, teaching the next generation of creators about the Internet of Things and development. “We wanted to give them that experience like it was in the days of writing BASIC when people would learn to code to invent their own video games,” Shelby said.

The diminutive BBC Micro:bit, roughly half the size of a credit card, is no slouch in terms of performance. Earlier this year, TechRepublic reported that the computer severely trounced a 1951 supercomputer known as the Harwell Witch. In one portion of the test, the Witch calculated three numbers in the Fibonacci sequence in 15 seconds. In that same interval, the Micro:bit calculated 6,843 numbers, 2,281 times more than the Witch.

Shelby was initially inspired by BBC’s ability to get the Micro:bit in the hands of 1 million children aged 11 or 12 in the United Kingdom in 2016. “I joined to go turn that [accomplishment] into an independent international foundation,” Shelby recalled.

The group estimates that, to date, 5 million children have used the technology. “There have been national rollouts in primary and secondary schools in Singapore, Croatia, Iceland, Denmark and, of course, the UK.”

The group estimates that, to date, 5 million children have used the technology. “There have been national rollouts in primary and secondary schools in Singapore, Croatia, Iceland, Denmark and, of course, the UK.”

The project has inspired an array of different types of projects with many taking advantage of the board’s 23-LED matrix and building, for instance, name badges. More adventurous creators will make projects such as two-player games. “We’ve seen two-player shooter games that had falling asteroids,” Shelby said. “What gets really interesting is that you have sensor technology you can use: three-axis accelerometers, three-axis magnetometers, light sensors and a Bluetooth radio.”

A group in Norway devised a game that took advantage of the Bluetooth radios. “With two boards, they made it so they made a game where you can shoot off one and the pixel would keep going off the screen over the Bluetooth radio to the other screen,” Shelby said. “It’s just incredible stuff the kids came up with.”

Many other the young makers take advantage of the sensing capabilities of the board. “You can connect the boards with alligator clips, so kids will do contact sensors for imaginary traffic applications or real traffic applications,” Shelby said. Measuring soil moisture is another popular application, as is connecting the Micro:bit to pumps for automatic irrigation for watering plants.

Another tier of applications focus on the physical world — measuring the acceleration of players in, say, football games. “You can measure how many times you’ve jumped, how hard you’ve kicked, how hard you’ve thrown,” Shelby said. “The sky is really the limit.”

The Micro:bit was also developed to facilitate development. It supports JavaScript, Python and draggable blocks of code in a web development interface. “Really kids with no supervision can start doing something with this quickly,” Shelby said. “Teachers who don’t have a technical background, as well.”

The technology was also designed to inspire girls as well as boys. “It is very gender neutral. Notice it’s not pink, but it has round edges. It has a well thought-through UX experience,” Shelby said. BBC Micro:bit studies in the United Kingdom found that programs using the device led to an overall 70 percent increase in the number of girls who signed up for computing courses. “Big difference, right? So that starts to affect the gender makeup of the STEM workforce,” he said. “It starts to affect the opportunity for kids that wouldn’t normally be interested in technology to consider becoming developers.”

The technology also helped inspire many children in developing countries. “We provide cheap development technology and modern tools — the same technology that you put into an actual production device: same chips, same kinds of sensors, the protocol stacks,” Shelby said. The hardware design is open source. “Someone could [use the Micro:bit as a foundation for] a product design and use the whole technology stack to go to market,” he added. “There are people in developing countries who would have never thought about building an IoT device who can get in the game. Some of the effects we’ll see in five years. Some of the people coming into the workplace in 10 years.”

About the Author

You May Also Like