Where is all of the IoT malware hiding?

Many of the most prominent IoT exploits are from security researchers. But that doesn’t mean that IoT malware isn’t already treacherous.

August 31, 2017

Given the significant attention dedicated to IoT security, there have been relatively few big IoT-specific attacks to hit the press. Exceptions include last year’s Mirai botnet, in which threat actors targeted the weak security of some 360,000 IoT devices to target DNS provider Dyn. A chunk of the internet went offline as a result. In 2010, there was Stuxnet — a zero-day exploit that caused physical damage to Iran’s nuclear centrifuges. And five years later, Russian IoT malware targeted Ukraine’s electrical grid, ultimately cutting off power to 230,000 people. Most recently, there was Stackoverflowin, software that commanded every online printer to print and then there was a leak of thousands of telnet credentials for IoT devices on Pastebin disclosed by Ankit Anubhav, principal security researcher at NewSky Security.

“While there is a lot of IoT threat talk, most of it amounts to presentations on ‘possible’ ways that IoT technology can be compromised,” Anubhav explained.

Security researchers often share their IoT-related exploits at the annual Defcon and Blackhat security conferences in Las Vegas. Examples include tales of hacked Jeeps, medical devices, semi trucks, drones and even car washes.

By contrast, the most notable cyberattacks of this year, from WannaCry to Petya, have targeted traditional IT infrastructure.

[IoT Security Summit, co-located with Blockchain360 and Cloud Security Summit, explores how industry-wide security, privacy and trust can be established to unlock the full potential of IoT. Get your ticket now.]

But a substantial amount of IoT malware is likely hiding in plain sight, said Kenneth Geers, a senior research scientist at Comodo Group and a NATO Cyber Centre ambassador. “My own thinking regarding IoT attacks is that if we are not seeing them, we are not looking in the right place,” he said.

Anubhav agrees, stating that the leak of IoT login credentials he recently disclosed was the tip of the iceberg of attacks he’s seen this year involving Internet of Things devices. “Maybe they are not all fancy, but they work,” Anubhav said. “And that’s all hackers want.”

There is evidence to support that such attacks are growing more common. Kaspersky indicates that IoT malware activity has more than doubled in the past year.

Among the active IoT-related security threats Anubhav has seen is a bug that allows a hacker to modify the temperature of the Heatmiser thermostat and malware known as NBotLoader that targets routers. There is also BrickerBot, a botnet (now in its fourth iteration) that renders insecure IoT devices unusable. To date, the malware has killed more than 2 million devices.

While consumer-centric attacks receive considerable attention, a significant portion of IoT malware likely relates to cyberwarfare, Geers explained. For one thing, modern military hardware tends to have computing power and networking capabilities. “When you think about it, any military ship, plane or tank has a slew of computers, processors, memory banks and network connections. There is a lot to attack and defend,” he said.

That could also include future nuclear missiles, which will have “some level of connectivity to the rest of the warfighting system,” as Werner J.A. Dahm, the chair of the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board told The Atlantic.

According to a March report in The New York Times, the United States has a program in place to target North Korea’s missile operations that could theoretically destroy the nation’s nuclear weapons before they are deployed.

While the details of such programs are rarely disclosed, IoT devices are likely commonly used for reconnaissance efforts to help opposing factions prepare the battlespace before combat. And during actual combat, parallel wars take place on computer networks. “I am not arguing that you can win a war with a cyberattack but you could win battles for sure if you infiltrate deeply into the network of your adversary,” Geers said.

Nevertheless, the fact that cyberwarfare has been a staple of modern cinema since at least the 1983 film WarGames leads many people to discount it as being unreal. “There are even people at Defcon don’t really understand cyberwar,” Geers noted. “Or they might think they understand it because they saw Die Hard 4 or something.”

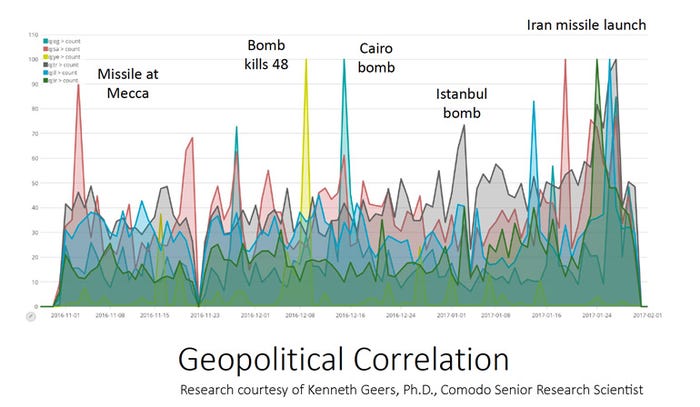

While headline-grabbing cyber attacks like Stuxnet that target industrial control systems are rare, data suggests that cyberwarfare is a constant reality. “Every time there is an invasion or a coup d’état, you can see that reflected in malware communications,” Geers explained. “As the conflict in Ukraine was getting more intense, so was the malware communications inbound to both Ukraine and Russia.”

The Internet of Things provides new opportunities for cyberespionage as well. As the number of networked IoT devices extends into the tens of billions of devices, it is inevitable that foreign powers will attempt to use some of those endpoints for data collection. After all, many come bundled with networked cameras and microphones that can all but do away with the need for traditional covert listening devices or hidden security cameras — or is at least blur the lines between them.

In any event, the role that the Internet of Things might play in future wars is difficult to assess, Geers explained. “Cybersecurity is really hard to predict because of the sheer number of attacks that are possible. I think the U.S. election last year is an example of that. I still don’t think we have figured out what happened there.”

About the Author

You May Also Like