Startup Creates Application Security Tools to Scale

An exec from ForAllSecure, who was part of the team that won DARPA’s Cyber Grand Challenge, sheds light on the use of autonomous technology in cybersecurity.

August 20, 2019

When it comes to cybersecurity, many executives want what they can’t have. For instance, they often want artificial intelligence without fully understanding what it is. And they want the best cybersecurity talent, but don’t want to pay too much for it. “We found a lot of cybersecurity leaders who wanted to hire MacGuyver but paid like McDonald’s,” quipped Forrester Principal Analyst Jeff Pollard in a recent podcast. Even the goal of hiring cybersecurity talent can be problematic. One recent count estimated the talent shortfall to be nearly 3 million cybersecurity workers globally. In any event, the demand for cybersecurity talent continues to grow. The majority of chief executive officers believe their organization’s success is dependent on having a sound digital strategy on the one hand and robust cybersecurity on the other. In 2017, Fortune found 71% of Fortune 500 executives considered the firms they manage to be technology companies, while 61% cited cybersecurity as a top concern.

Amidst all of these trends is a growing acknowledgment among tech executives and the general public that artificial intelligence is a transformational technology — for its business potential as well as for its potential to continue automating many tasks traditionally performed by humans. Several cybersecurity vendors describe their products as AI-enabled.

There tends to be, however, widespread disagreement about what, in particular, artificial intelligence is, let alone how to best deploy it — whether in cybersecurity or elsewhere. At the same time, many organizations struggle to find application security tools that can keep up with their needs. The use of security analytics tools is, however, widespread, according to a 2017 Ponemon Institute report underwritten by SAS. These tools range from security and event management to network behavior analysis, user behavior analytics, and endpoint detection and response. In all, close to 90% of the IT and cybersecurity professionals surveyed used at least some form of analytics.

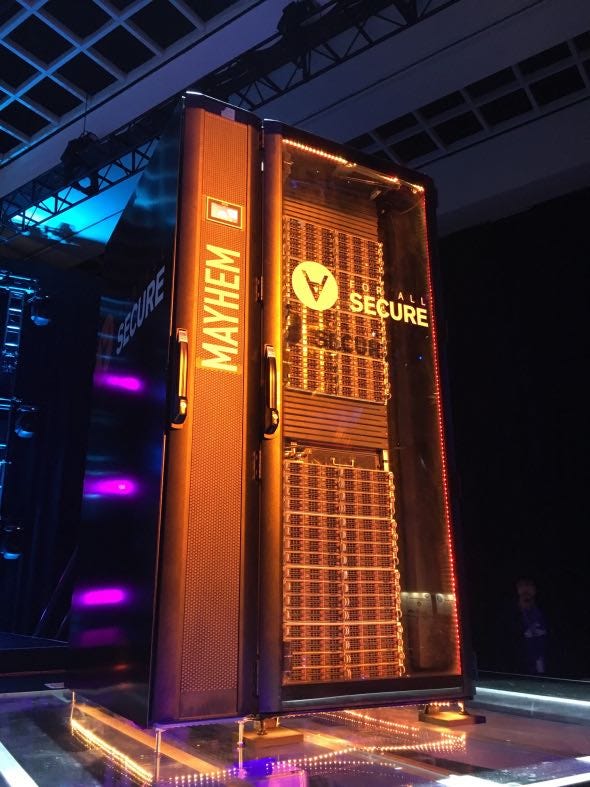

David Brumley, chief executive officer at ForAllSecure, has experience working a wholly different animal. Mayhem, the company’s autonomous computing system, can find software bugs and address them. Brumley led a research team that won the $2 million top prize at the DARPA Cyber Grand Challenge in 2016. To be crowned as the winner of the contest, the team had to develop an automated system that bested competitors at autonomously finding, patching and exploiting software vulnerabilities.

David Brumley

Brumley, a Carnegie Mellon University professor currently on leave to focus on ForAllSecure, prefers to call Mayhem “autonomous security” rather than “artificial intelligence.” “We’re doing things that normally a human would make a decision on. But that doesn’t mean we’re employing, deep neural nets or something like that,” he said. “Autonomy can be like autopilots, which have been around forever.”

The vision is to “augment the human workforce with machines,” Brumley said.

The company’s website describes the technology as an “assisted intelligence behavior testing solution.”

While interest in application security tools in general and automated vulnerability detection and patching, in particular, is on the upswing, confusion often persists when it comes to using this technology. ForAllSecure’s product is based on fuzzing and symbolic execution. Fuzzing is using random commands and inputs to see how they affect a program. Symbolic execution, on the other hand, involves analyzing software to see which “inputs cause each part of a program to execute,” as Wikipedia puts it.

The longer a company uses an autonomous-security product to evaluate software, the deeper it goes. “The first question I get asked is: How long do you run it? When do I stop?” Brumley said. “And the real answer to this is you can run them forever.”

A one-minute video from the British cybersecurity firm Pen Test Partners shows the ability of a fuzzing attack targeting a moving Tesla’s CAN bus. Within 30 seconds, the car grinds to a halt.

But an adversary could launch a fuzzing campaign for weeks or longer before moving onto the next phase of an attack. “Let’s say you run a fuzzing campaign for a week. If an attacker runs a campaign for two weeks, maybe he finds something you don’t,” Brumley said. “That really blows many people’s minds, because they want a checkmark as opposed to setting up the automated process where it’s just always trying to find [vulnerabilities].”

Technology like Mayhem can also help organizations develop a more nuanced view of software patching. Instead of viewing software patching in black-and-white terms, Mayhem continuously assesses software vulnerabilities after a patch is applied to determine what new vulnerabilities it introduces.

In 2014, Carnegie Mellon researchers used the Mayhem to test each application in Debian, a typical Linux distribution. The software discovered almost 14,000 vulnerabilities in under a week.

Similarly, Google has made an automated fuzzing tool, known as ClusterFuzz open source. ClusterFuzz has helped the company identify some 16,000 bugs. In 2017, Microsoft opened its fuzz testing product to the broader public after having used it internally.

“We’re bringing to market the ability to find vulnerabilities and, when people apply patches, reassess them automatically,” Brumley said. “Lots of people talk about finding vulnerabilities. We prove it. We can show: ‘When you give this [input] to the program, it’ll crash. If you give this [other input] to the program, we can show we can take control of it.”

Internet of Things devices, which frequently make use of insecure software, are a good fit for Mayhem. To date, however, many of the organizations interested in ForAllSecure are interested in their software supply chain. “Initially, we kind of expected healthcare, financial organizations,” he said. But the software can also help organizations tame software supply chain complexity. A company that makes a military aircraft, for instance, is as much of an integrator as it is a manufacturer. It works with scores of suppliers, which in turn have their roster of suppliers.

Assessing the software supply chain is more straightforward than analyzing a hardware supply chain. “Figuring out there’s a backdoor in hardware is very expensive and requires a high level of expertise,” Brumley said. “But when you start to check out the code for vulnerabilities, that’s something that you demonstrate is possible automatically.”

ForAllSecure’s ability to do just that helped it raise $15 million in series A funding led by New Enterprise Associates. Before that point, the company had reached profitability, Brumley said.

While he is upbeat about his firm’s prospects, Brumley acknowledged that “with any new transformational technology, there’s a lot of education.” That is the case with artificial intelligence at large, where organizations’ executives become excited about the potential of machine learning for their business. Later, however, they can realize their data science team needs to be expanded before the company can make sense of the data they are gathering. “You can get benefits out of AI, but it’s not just a black box you plug in,” Brumley said. To enable cybersecurity researchers to have realistic expectations concerning the capabilities of emerging technology and the requirements to deploy it successfully requires education, Brumley added. “We want to teach people what it can do.”

About the Author

You May Also Like